Judging by my webserver’s logs, almost nobody actually bothers to click through the blog-carnival host’s site to read my Giant’s Shoulders” posts. This could be due to a secret conspiracy involving famous bloggers and several shadowy government agencies. I suppose, though, that there’s a chance that simply nobody but me is that interested in non-medical microbiology. Well…today’s post is an attempt to disprove that concept, for what aspect of non-medical microbiology could be more universally appealing than beer?

Unfortunately, in the middle of trying to assemble this posting, I see the February host has decided to put the carnival up a day early, undercutting my experiment. See, I told you it was a conspiracy! I suspect the Secret Cabal of Popular Bloggers was getting pressure from the Trilateral Comission, the NSA, and Pepsico® to silence me, so they had to do it. At least being forced to miss one, I am now free from the “I’ve been posting to these since the beginning, I can’t miss one now!” treadmill.

That means, loyal readers, that you get to see this post a month before everyone else! Hooray! Stick it to The Man™! Comically paranoid rantings aside, it also means I can split this up into more than one post, which may be more readable considering how much ground the article in question actually covers. Today’s Classic Scientific Paper is:

Nathan, L:”Improvements in the fermentation and maturation of beers.”; 1930; J. Inst. Brewing; 36; pp538-550

I ran across this reference recently while working my way through an industrial microbiology text[1] that I checked out of the campus library. According to the author of this text, “The use of cylindro-conical vessels in the brewing of lager was first proposed by Nathan (1930)[…]”, referring to the now-ubiquitous style of metal fermenter seen in small brewpubs and “MegaBladderwashCo” large-scale industrial breweries alike. Based on this I had expected the reference to be a digression on the design, construction, and testing of the fermenter. When inter-library loan managed to get me a copy of the paper, I found something much more involved.

The paper is a presentation made by Dr. Leopold Nathan in 1930 to the Scottish section of the Institute of Brewing. The topic was not simply a fermenter design but the entire “Nathan System” of brewing which appears to be the basis of modern large-scale brewing, especially for Lager-type beers. At this point, Dr. Nathan had apparently already been developing this system for about thirty years (apparently starting with a German patent in 1908, which I’ve yet to find a copy of), so as you might guess it was not just a single invention but a whole collection of them. Compared to the more rustic techniques frequently in use at the time, the “Nathan System” of brewing promised to provide faster production, more consistent results, and a better final product. It does this mainly by improving the removal of “trub” (the cloudy bits of protein and such that settle out of the malt-water – the “wort” – after you boil it), preventing infection of the beer with undesirable organisms during the cooling, hops-infusion, and aeration, and by eliminating the need to “age” the brew to make it palatable. The most important improvement in the “Nathan Process” seems to be how he treats the wort between boiling and “pitching”.

—

For anyone unfamiliar with the brewing process, here’s a Grossly Oversimplified review of the steps:

- Boil some malt-sugar dissolved in water to sterilize it and to help coagulate the “trub” proteins so they’ll settle out of the liquid.

- Cool the malt solution and aerate it so that the yeast will grow in it.

- “Pitch” your yeast into the now-cooled-and-aerated malt-water, in a container that will keep air out while letting out the carbon dioxide bubbles that the yeast will give of during the fermentation

- Wait until the yeast get done fermenting, then put the resulting liquid into bottles/kegs/casks/whatever.

—

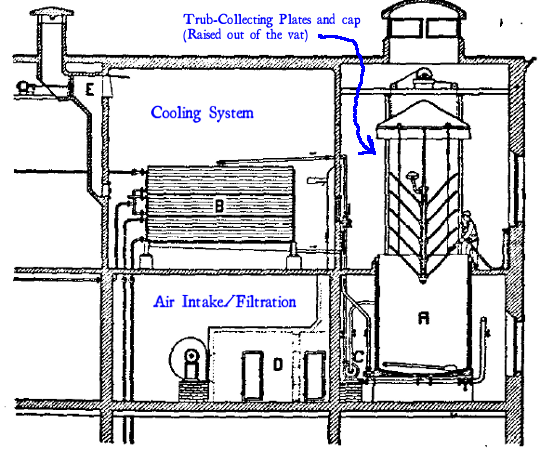

I’ve added a couple of labels to that image from the paper, which I’m guessing was itself copied from a contemporary patent of Dr. Nathan’s. There are two purposes to this part of the Nathan Process – To cool and aerate the wort quickly without exposing it to risk of contamination, and to move trub and volatile sulfur compounds that would otherwise make the brew taste and smell funny. The hot boiled wort is pumped directly into an insulated vat (labelled “A” in the diagram) from the boiling kettle. At this stage the wort is hot enough to prevent anything from landing in it and growing. Then, the hot wort is pumped from the top of this vat into a clean-room containing a cooling device that the wort is poured on, cooling and aerating it as it flows through. Infection is prevented here by the fact that the room has a continuous stream of “sterilized” (or at least well-filtered) air, which is exhausted through the vent in the ceiling. The cooled, aerated wort is then pumped back out of the room and into the bottom of the insulated container below the still-hot wort.

Because of the large open cooling room with its constant stream of clean air, the cooling and aeration step also allows the volatile sulfurous compounds of “jungbukett” (The “Bouquet of Youth”; the unpleasant smells and tastes of immature beer, described in this paper as ‘onion-like’) to evaporate off and be carried away. Since waiting for these compounds to break down was apparently a primary reason for having to “age” lager before selling it, this not only improves the quality but eliminates the need to store the beer for months after fermentation.

The now-chilled wort then rests back in vat “A” and the trub settles out onto horizontal plates inside the vat, where it stays behind when the clarified wort is pumped out to the fermenters.

I did some poking around, and this appears to be what is described in US Patent# 1,581,194 (application filed in August of 1921), in case you are bored and want to look that up. If not, or if you don’t want to deal with the frustrating hassle of trying to view TIFF files in your browser, I intend to provide a followup post with some more details of the process and some interesting bits I found in it, and I’ll include a pdf of the patents, assuming anyone wants them.

Oh, one last thing – I’ve had no luck getting any biographical information about Dr. Leopold Nathan. Unfortunately when you search for “Leopold Nathan”, the results are clogged with references to a murdering smartass named “Nathan Leopold” instead. Doesn’t Google™ realize that brewmeisters are far more important than obscure murderers? No pictures of him, either, so I can’t even say whether his hairstyle is cooler than Eduard Buchner’s or not.

[1] Stanbury PF, Whitaker A, Hall SJ:”Principles of Fermentation Technology (2nd edition)”; 1995; Elsevier Science, Ltd; Tarrytown NY