The Giant’s Shoulders blog carnival is coming up in two days, and I just realized I still haven’t gotten a post up for it yet. So, here it is.

The Giant’s Shoulders blog carnival is coming up in two days, and I just realized I still haven’t gotten a post up for it yet. So, here it is.

I put up some quick reviews of several classic microbiology-methods papers for the previous edition of this blog carnival, but didn’t actually get around to putting up the one for what is almost certainly the most well-known microbiology technique: “The Gram Stain”. So, this post is about it:

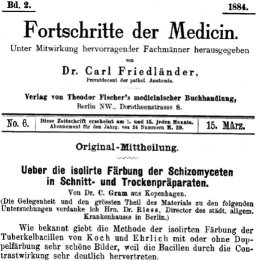

Gram HC: “Ueber die isolirte Faerbung der Schizomyceten in Schnitt- und Trockenpraeparaten”; Fortschritte der Medicin; 1884; vol 2, pp 185-189

That’s “Regarding the Isolational(?) Coloring of Schizomycetes in Cut- [i.e. tissue sections] and Dried Preparations” in “Medical Progress”. The translation hosted by the American Society for Microbiology uses the word “Differential” where I’ve put “Isolational” – which is probably not quite right either but it’ll have to do for now – but I’ll get to that in a moment.

If you’ve ever been exposed to microbiology labwork before, you’ve almost certainly done or at least watched a procedure referred to as a “Gram stain”. In brief, you smear your sample with bacteria on a glass slide and bake it on, then you dump some purple stuff on it, them some brown stuff, then you rinse it briefly with alcohol, then you dump on some pink stuff, and then rinse it in water and look at it under a microscope. Bacteria that stay the original dark purple-blue color of the original purple/brown stuff are considered “Gram Positive”, and those that don’t instead appear the pink color of the last stain, and are considered “Gram Negative”. Many textbook authors and microbiology instructors will breathlessly proclaim that the Gram Stain reveals two “fundamental” categories of bacteria, but I’ll spare you my rant about that.

Properly speaking, this isn’t actually Gram’s stain, as described in his original paper. The modern variations that we’re all taught in microbiology class were developed later, and I believe they are nowadays based mainly on Victor Burke’s 1922 paper on the subject[1].

Regarding the title of the paper: “schizomycete” is what they used to call most kinds of bacteria. “Mycete” meaning “fungus”, as bacteria were assumed to be “plants without chlorophyll” just like molds and mushrooms, and “Schizo-” meaning “split in two”, since bacteria reproduce by splitting into two cells rather than by producing spores like “other” fungi. I say “most” because things like cyanobacteria (“blue-green algae”) or Green Sulfur Bacteria would have been referred to as “Schizophyta” (“fission-plants”). What Gram was originally trying to do wasn’t to differentiate one kind of bacteria from another, either, but to make it easy to tell bacteria from from the nuclei of cells in bacteria-infected tissue.

For that matter, Gram was really metaphorically standing on the shoulders of Koch and Erhlich, as he was building on their technique for staining “tubercle bacteria” – that is, tuberculosis-causing members of the genus Mycobacterium. Gram mentions that you need to stain this type of bacteria for the “usual” 12-24 hours to make this work, incidentally, as opposed to a few minutes for other “schizomycetes”. This suggests that you are expected to have some idea of what you’re going to find before you use the stain, as opposed to the modern implementation which is supposed to tell you something about what kind of bacteria you’re finding.

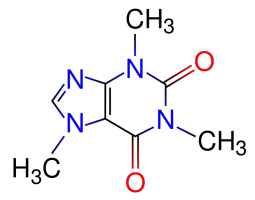

Still, Gram does report that some bacteria take the stain and some don’t, giving us a preview of the “differential” character of the modern version. He specifically notes typhoid and some causes of bronchial pneumonia fail to hold the stain. Given that Typhoid Fever is caused by a strain of the “Gram-negative” butt-bacter Salmonella enterica, and there are a number of “Gram negative” bacteria as well as “Gram positive” that can cause pneumonia, this makes sense. He also does mention the use of Bismarck Brown R a.k.a. Vesuvine as a counterstain in order to make the nuclei of the infected cells brown in contrast to the dark blue of the infectious bacteria in the tissue.

For much of the century-and-a-quarter since Gram’s publication, the question of why the Gram stain works was thoroughly investigated, and even today I occasionally hear or read assertions to the effect that the Gram Stain isn’t well understood. I disagree with this just as I think its importance to bacterial identification is grossly overblown, and if you want to know why, I have a previous post all about why the Gram stain works and how we know. You may or may not also be interested in an older post regarding whether or not “acid-fast” bacteria like the ones that cause tuberculosis (which don’t stain at all when using the modern version of the Gram stain) are “Gram Positive” or not. As always, if you spot any errors or have any questions, please let me know…

[1] Burke V: “Notes on the Gram Stain with Description of a New Method.” J Bacteriol. 1922 Mar;7(2):159-82.

Microbiology is the dominating topic of this particular blog, but I don’t think I’ve ever addressed what I consider to really count as “micro”biology. This isn’t necessarily an obvious topic. My old “Microbiology” book from 8 years ago, plus the textbook from last year’s “Pathogenic Microbiology” class both contained large sections discussing organisms that are visible without a microscope. Heck, the “Pathogenic Microbiology” text even had a whole section on spider and insect bites. And, tapeworms? Since when is “over 30 feet long” considered “micro”? As I like to say: It’s time for Microbiology to grow up and move out of Medicine’s basement.

Microbiology is the dominating topic of this particular blog, but I don’t think I’ve ever addressed what I consider to really count as “micro”biology. This isn’t necessarily an obvious topic. My old “Microbiology” book from 8 years ago, plus the textbook from last year’s “Pathogenic Microbiology” class both contained large sections discussing organisms that are visible without a microscope. Heck, the “Pathogenic Microbiology” text even had a whole section on spider and insect bites. And, tapeworms? Since when is “over 30 feet long” considered “micro”? As I like to say: It’s time for Microbiology to grow up and move out of Medicine’s basement.