Gram stain, Gram stain, Gram stain! Bah. I think it’s time Microbiology grew up and moved out of Medicine’s basement.

Sure, the Gram stain[1] has its uses, but the procedure is grossly over-hyped. “[…]the most important stain in microbiology[…]”[2]! “[…]it is almost essential in identifying an unknown bacterium to know first whether it is Gram-positive or Gram-negative.”![3] “The Gram Stain reaction is an especially useful differentiating characteristic.[…]The Gram reaction turns out to be a property of fundamental importance for classifying bacteria phylogenetically as well as taxonomically.”![4] “[…]differentiates bacteria into two fundamental varieties of cells.”![5] “The Key to Microbiology“![6] [emphasis added…]

Bah! Sure, the Gram stain has its uses, but the hype it gets (even 125 years after its invention) is ridiculous. It’s worse than Harry Potter!

You really want to know what the Gram reaction tells you? Really? Okay, here it is:

A “Gram Positive” reaction tells you that your cells have relatively thick and intact cell walls

A “Gram Negative” reaction tells you that they don’t.

That’s it. That’s about all you can reliably infer from the Gram stain.

Previously, I put up a post describing what was my understanding of the conventional view of why the Gram stain works. Today, I’ll give you a much more detailed – and more correct – explanation of why it works as well as what its real significance is to identification of microbes. But first, a brief one-paragraph rant on why I think the Gram stain has such a hold on microbiology teaching.

I blame the fact that microbiology education is still largely in the shadow of medical technology education. When you artificially exclude the 99+% of organisms that aren’t associated with human diseases, the tiny number left do, indeed, seem to largely separate into two phylogenetic categories. Judging by what I’ve encountered thus far, it seems you get a lot of Proteobacteria (especially ?-Proteobacteria, like E.coli), which are “Gram-negative”. You also get a lot of Firmicutes (Bacillus, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, etc.), and a couple of scattered Actinobacteria (Mycobacterium, for tuberculosis and leprosy, Corynebacterium for diptheria…). Both of these are considered “Gram-positive” (although if you use the standard procedure these days, the Mycobacteria may show no reaction at all). That’s, what, 3 phyla out of about 25 eubacterial and archael phyla? If we throw in Syphilis and Chlamydia, that’s still only 20% or so of the currently recognized prokaryotic phyla. If your microbiology classes assume everybody is training to be a medical technologist or clinical microbiologist, then the Gram stain becomes inflated in importance.

Enough of that – here’s a quick review of how the Gram stain works. Solutions of “Crystal Violet” (a purple dye) and Iodine are applied to cells fixed to a slide, where they soak in and precipitate in the cells. A “decolorizer” (usually ethanol) is applied to see if it will wash this dye precipitate out of the cells. A different, lighter-colored dye (such as safranin) is added so that the cells which DO have their dye washed out can be seen as well. In the end, “Gram positive” cells are a dark purple from the crystal violet/iodine that was not washed away, and “Gram negative” cells are not dark purple. (Usually they are pink, from the safranin, assuming that’s the dye used as the counterstain.)

Note that this does not differentiate cells into “two fundamental types” as is often claimed. You actually get four types: Groups of cells that are normally always “Gram positive”, Groups of cells that are normally always “Gram negative”, Groups of cells that are normally sometimes “Gram positive” and sometimes “Gram negative” (“Indeterminate”, or as I like to call it, “Gram-biguous”), and groups of cells that are normally NEITHER Gram-positive nor Gram-negative, like Mycoplasma, which aren’t dyed at all by the process. Incidentally, phylogenetically speaking, Mycoplasma is one of the “Gram positive” Firmicutes, just like Bacillus and Staphylococcus.

It’s kind of interesting to me that the Gram stain reaction has been such a mystery up until a century after its invention. What is it that makes “Gram positive” cells retain the dye while “Gram negative” ones don’t? Along the way, it seems like nearly every part of the bacterial cell was hypothesized to be the reason for the Gram reaction – lipids, carbohydrates, nucleic acids, “Magnesium ribonucleates”, and so forth. Davies et al, 1983, includes a table listing many of these and referencing historical papers making the claims. The fact that the reaction had something to do with the cell wall seems to go back quite a while, though the “Magnesium ribonucleates” idea doesn’t seem to have been entirely abandoned until the mid-1960’s[7]. It was also hypothesized that the “Gram positive” cells simply absorb more dye and therefore take longer to “decolorize”.

It turns out that “Gram-positive” cells actually don’t, necessarily, take up more dye than Gram negative ones. This was tested by taking a set concentration of bacterial cells and adding them to a set concentration of dye. After letting them soak, the samples were centrifuged to remove the bacteria, and the amount of dye found to be missing from the liquid was taken as the amount absorbed by the cells. They found that some Gram negative cells actually took up more dye than the Gram positives did. So much for that idea.[8]

Even relatively recently, I’ve seen it written that the bacterial cell wall, specifically, is what holds onto the stain, but even that turns out not to be true. Although the cell wall is the structure that seems to be responsible for the Gram reaction, in the late 1950’s it was demonstrated that it was not actually the staining of the cell wall that caused the reaction, but rather the ability of the cell wall to keep the decolorizer out of the cell.[9]

Apparently, the Crystal Violet/Iodine complex itself doesn’t even play a vital role. The complex apparently dissolves again more or less instantly as soon as the decolorizer touches it[10], and it’s even possible to differentiate “Gram positive” and “Gram negative” with simple stains like methylene blue or malachite green, if you’re clever about it[11]. The latter authors set up a clever test with crushed cell material, dye, and paper chromatography. They had the decolorizer soak into the paper, past a spot where dye-soaked cell material from Gram-positive and Gram-negative cells was placed, and watched for obvious differences in the amount of time it took the dye to be carried out by the decolorizer. Incidentally, my quick examination of this paper makes it look like cheaper 100% isopropyl alcohol (“rubbing alcohol”) might be slightly better than the standard 95% ethanol for Gram stains.

– INTERLUDE –

So, here we are at 1970 or so, and we already know that the Gram reaction is entirely based on how well the cell wall structure prevents organic solvents (like ethanol) from soaking into the cell to dissolve the dye complex. Yes, the mystery of why the Gram stain works in normal cells was largely solved by the Nixon era.

A few corners of the mystery remained, though. Why do “old” cultures of “Gram positive” cells often end up staining “Gram negative”, for example? Why do some kinds of cells seem to be sometimes Gram positive and sometimes Gram negative in the same culture? What, exactly, is really happening to the cell, deep down, during the staining process?

In 1983, the Gram Stain made the great technological leap into the 1930’s, when a variation of the technique was devised which allowed the Gram Stain to be observed by electron microscopy[12]. Using a funky platinum compound in place of iodine, the electron microscope reveals exactly where the dye complex is at any particular stage of the Gram stain process. Using this technique, it was possible to see how the decolorizer disrupts the outer membrane of classically-Gram-negative organisms and to see that the decolorizer potentially damages the cell wall and interior membrane, possibly allowing cell material to leak out (or decolorizer to get in and dissolve the dye complex). It was also seen that the dye complex permeates the entire cell, not just the cell wall.[13]

If you’ve been wondering about the sometimes-Gram-positive-sometimes-Gram-negative cells, the same technique was also used to investigate this. As suspected, it turns out that the “old cultures become Gram negative” problem is due to the cell walls breaking down as the culture ages. Bacteria are continuously, simultaneously, building up and tearing down their cell walls, in order to be able to grow and divide. As nutrients run out, the bacteria run out of material to rebuild cell walls, while the cell-wall degrading enzymes keep on chugging. Breaks in the cell wall occur, and through these breaks the decolorizer can get in and rapidly dissolve the dye. Actinobacteria can have a similar problem, but rather than only being in “old” cultures, apparently weaknesses appear briefly during cell division, and if a particular cell happens to be at this stage of growth when you stick it on a slide, heat-fix, and Gram stain it, the weakness at the septum where the division is occuring can crack and allow the decolorizer in, resulting in a “Gram negative” response even while surrounding cells of the same kind might still be “Gram positive”.[14]

This brings us to archaea and some eukaryotes (i.e. yeasts). Yeasts stain “Gram positive” normally. Although their cell walls are completely different chemically than bacterial cell walls, they are quite thick (microbially speaking). Poor, neglected Archaea seem to be all over the place in terms of Gram reaction. Since their Gram reaction doesn’t tend to correlate to any particular phylogenetic grouping[15], it seems nobody really pays much attention to their Gram stain reaction. On the other hand, and on the subject of “Gram-biguity”, I thought the investigation of Methanospirillum hungatei[16] was interesting. M.hungatei is an archaen that grows in chains. When Gram-stained, the cells on the ends of the chains are “Gram positive”, while the others have no Gram reaction at all. It turns out that the chains are covered by a sheath, and the only contact with the outside world is through thick “plugs” in the cells at the ends of the chains. These “plugs” act like thick cell walls, allowing the Gram stain dye material to soak in but excluding the decolorizer, while the sheath keeps the rest of the cells from soaking up any stain at all.

There you have it – a relatively detailed history and explanation for the Gram stain, and you didn’t even have to get through some obnoxious paywall to read it. Aren’t you lucky?

Comments, suggestions, and corrections, as always, are welcome.

[1] Gram, HC.”Ueber die isolirte Faerbung der Schizomyceten in Schnitt-und Trockenpraeparaten.” Fortschitte der Medicin. 1884 Vol. 2, pp 185-189.

[2] Popescu A, Doyle RJ. “The Gram stain after more than a century.” Biotech Histochem. 1996 May;71(3):145-51.

[3] Brock TD, Madigan MT, Martinko JM, Parker J. “Biology of Microorganisms (7th Edition).” 1994. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ pg. 46

[4] ibid, pg. 715

[5] Beveridge TJ.”Use of the gram stain in microbiology.” Biotech Histochem. 2001 May;76(3):111-8.

[6] McClelland, Rosemary. “Gram’s stain: The key to microbiology – isolate identification method – Tutorial” Retrieved 20070810 from http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m3230/is_4_33/ai_74268506/print

[7] Normore WM, Umbreit WW.”Ribonucleates and the Gram stain.” J Bacteriol. 1965 Nov;90(5):1500.

[8] BARTHOLOMEW JW, FINKELSTEIN H:”CRYSTAL VIOLET BINDING CAPACITY AND THE GRAM REACTION OF BACTERIAL CELLS.” J Bacteriol. 1954 Jun;67(6):689-91.

[9] BARTHOLOMEW JW, FINKELSTEIN H.”Relationship of cell wall staining to gram differentiation.” J Bacteriol. 1958 Jan;75(1):77-84.

[10] LAMANNA C, MALLETTE MF. “CHROMATOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS OF THE STATE OF ASSOCIATION OF THE DYE-IODINE COMPLEX IN DECOLORIZATION SOLVENTS OF THE GRAM STAIN.” J Bacteriol. 1964 Apr;87:965-6.

[11] Bartholomew JW, Cromwell T, Gan R.”Analysis of the Mechanism of Gram Differentiation by Use of a Filter-Paper

Chromatographic Technique.” J Bacteriol. 1965 Sep;90(3):766-77.

[12] Davies JA, Anderson GK, Beveridge TJ, Clark HC.”Chemical mechanism of the Gram stain and synthesis of a new electron-opaque marker for electron microscopy which replaces the iodine mordant of the stain.” J Bacteriol. 1983 Nov;156(2):837-45.

[13] Beveridge TJ, Davies JA.”Cellular responses of Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli to the Gram stain.” J Bacteriol. 1983 Nov;156(2):846-58.

[14] Beveridge TJ. “Mechanism of Gram Variability in Select Bacteria.” J Bacteriol. 1990 Mar;172(3):1609-20.

[15] Beveridge TJ, Schultze-Lam S. “The response of selected members of the archaea to the gram stain.” Microbiology. 1996 Oct;142 ( Pt 10):2887-95. (Abstract)

[16] Beveridge TJ, Sprott GD, Whippey P. “Ultrastructure, inferred porosity, and gram-staining character of Methanospirillum hungatei filament termini describe a unique cell permeability for this archaeobacterium.” J Bacteriol. 1991 Jan;173(1):130-40.

Expired JellO®! Deadly Poison, or Merely Debilitating? Can a human being withstand the toxic load of an *entire box* of it? Would he suffer embarassingly loud and messy gastrointestinal distress, or would immediate organ failure set in before this could take place? STAY TUNED TO FIND OUT!…

Expired JellO®! Deadly Poison, or Merely Debilitating? Can a human being withstand the toxic load of an *entire box* of it? Would he suffer embarassingly loud and messy gastrointestinal distress, or would immediate organ failure set in before this could take place? STAY TUNED TO FIND OUT!…

Last night, I plucked from the depths of my pantry an expired-2½-years-ago box of sugarless orange-flavored gelatin with which to begin this investigation. I blew the layer of dust off of the box, and carefully opened it, half-expecting to find some strange mutant gelatin-beast had developed in it over the years since expiration. One hand poised to protect myself should the creature leap from the box to eat my face in anger of being disturbed, I was both relieved and slightly disappointed to find nothing more than a foil packet containing what sounded like perfectly ordinary gelatin-powder. The packet proved to be intact, and the happy orange powder poured into a freshly-cleaned dish in a manner perfectly imitating that of wholesome non-expired gelatin. I dismissed the faint demonic snickering sound I seemed to hear as a figment of my fevered imagination and prepared the gelatin powder in the usual manner.

Last night, I plucked from the depths of my pantry an expired-2½-years-ago box of sugarless orange-flavored gelatin with which to begin this investigation. I blew the layer of dust off of the box, and carefully opened it, half-expecting to find some strange mutant gelatin-beast had developed in it over the years since expiration. One hand poised to protect myself should the creature leap from the box to eat my face in anger of being disturbed, I was both relieved and slightly disappointed to find nothing more than a foil packet containing what sounded like perfectly ordinary gelatin-powder. The packet proved to be intact, and the happy orange powder poured into a freshly-cleaned dish in a manner perfectly imitating that of wholesome non-expired gelatin. I dismissed the faint demonic snickering sound I seemed to hear as a figment of my fevered imagination and prepared the gelatin powder in the usual manner. I took up my electric kettle, containing distilled water, and threw the switch. Seconds passed into minutes. Minutes passed into more minutes. Then, the water began boiling vigorously, and I applied one cup (8 fluid ounces) of this to the dish of powder, stirring it with a tablespoon. It seemed to take at least two minutes of continuous stirring, but the deceptively innocent-looking powder finally dissolved without the slightest scent of brimstone. As prescribed by the instructions on the box, I added a further 8 fluid ounces of cold water (from the tap of my kitchen sink), stirred briefly to mix, and placed the dish in the refrigerator to gel overnight.

I took up my electric kettle, containing distilled water, and threw the switch. Seconds passed into minutes. Minutes passed into more minutes. Then, the water began boiling vigorously, and I applied one cup (8 fluid ounces) of this to the dish of powder, stirring it with a tablespoon. It seemed to take at least two minutes of continuous stirring, but the deceptively innocent-looking powder finally dissolved without the slightest scent of brimstone. As prescribed by the instructions on the box, I added a further 8 fluid ounces of cold water (from the tap of my kitchen sink), stirred briefly to mix, and placed the dish in the refrigerator to gel overnight. Day broke, and this very afternoon I took the now solidified mass from the refrigerator. This was it. My last chance to avoid whatever hellish abuses this disturbingly orange substance had planned for me. But no…it was far too late to turn back now. I took up my spoon, and devoured every last bit of happy orange jiggliness.

Day broke, and this very afternoon I took the now solidified mass from the refrigerator. This was it. My last chance to avoid whatever hellish abuses this disturbingly orange substance had planned for me. But no…it was far too late to turn back now. I took up my spoon, and devoured every last bit of happy orange jiggliness.

I always find it interesting to go back and see the earlier stages of scientific endeavors – especially as relates to my own interests. There always seem to be things that have since been forgotten, abandoned, or glossed over in them.

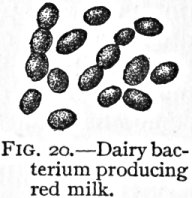

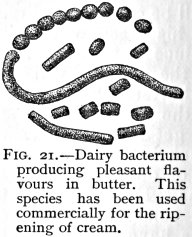

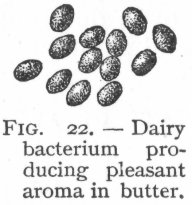

I always find it interesting to go back and see the earlier stages of scientific endeavors – especially as relates to my own interests. There always seem to be things that have since been forgotten, abandoned, or glossed over in them. H.W. Conn seems to have been most interested in dairy microbiology, so there is a substantial amount of space devoted to it. I’ve heard of “blue milk” before (Yummy!….Pseudomonas?), but not Red or Yellow milk. He also devotes space to discussing the affect of “good” (and “bad”) bacterial cultures on butter, cream, and cheeses. I’m not even sure if butter is cultured these days, or if they just churn it up fresh and cold with minimal growth. Dangit, one of these days we’re just going to have to move somewhere we can keep a miniature dairy cow so I can do some experimentation with real unpasteurized fresh milk.

H.W. Conn seems to have been most interested in dairy microbiology, so there is a substantial amount of space devoted to it. I’ve heard of “blue milk” before (Yummy!….Pseudomonas?), but not Red or Yellow milk. He also devotes space to discussing the affect of “good” (and “bad”) bacterial cultures on butter, cream, and cheeses. I’m not even sure if butter is cultured these days, or if they just churn it up fresh and cold with minimal growth. Dangit, one of these days we’re just going to have to move somewhere we can keep a miniature dairy cow so I can do some experimentation with real unpasteurized fresh milk. Bacterial phylogeny was so quaint back then. “Bacillus acidi lacti.” Ha! I love it. Interestingly, the term “Schizomycete” doesn’t appear anywhere in the text, though that may or may not be because it was considered unnecessarily technical for the intended audience. There’s actually very little about microbiological methods, too, which is the one major disappointment for me. Oh well, still interesting stuff. Conn actually mentions various “industrial” uses of bacteria including retting (soaking fibrous plants like flax or hemp so that bacteria eat the softer plant material to free the fibers), the roles of different bacterial cultures in curing tobacco, and even a fermentation in the production of opium (which Conn says is fungal rather than bacterial).

Bacterial phylogeny was so quaint back then. “Bacillus acidi lacti.” Ha! I love it. Interestingly, the term “Schizomycete” doesn’t appear anywhere in the text, though that may or may not be because it was considered unnecessarily technical for the intended audience. There’s actually very little about microbiological methods, too, which is the one major disappointment for me. Oh well, still interesting stuff. Conn actually mentions various “industrial” uses of bacteria including retting (soaking fibrous plants like flax or hemp so that bacteria eat the softer plant material to free the fibers), the roles of different bacterial cultures in curing tobacco, and even a fermentation in the production of opium (which Conn says is fungal rather than bacterial).