It’s not midnight here yet, I’m still on time!

Hello, “Just Science 2008” subscribers and everyone else. My life is insane at the moment but dagnabbit I’m going to do my best to get at least one post up on a scientific topic every day from today (Monday, February 4th) until Friday…

Today’s post is in the form of a gedanken experiment.

First, imagine the following:

- Some “entities” existing somewhere

It doesn’t matter what “entities” you are imagining, whether they are products in a market setting, or data structures in a computer program, or topics of discussion on a news broadcast. All that matters is that there can be more than one of them.

- A mechanism by which these “entities” are copied (and, optionally, also sometimes removed)

Products are manufactured or recalled, data structures can be copied or deleted, additional news anchors can be added to comment on a topic or conversely may shut up about them…

- At least one mechanism by which changes can occur between or during copies

Product designs can be changed, a computer program may consult a “random number” generator and use it to make small changes in the data structure, scriptwriters may alter the news anchor’s teleprompter messages…

- Some aspect of the “entities” that affects the rate at which they are copied (and/or, optionally, removed).

Demand by buyers in the market results in ramping-up of production, a computer program may perform some test or comparison of a data structure and use the result to determine how many copies of it to make (or whether or not to delete it), news topics that result in more people watching are repeated more often while those that people tune out from are dropped from the schedule…

What happens to this group of “entities” over time should be obvious. Taking the example of products in a market, producers introduce a variety of products (the group of “entities” in this example) and buyers examine their characteristics and, based on which ones they like, buy some of them. The producers observe which kinds of products are selling more and make more of those, while reducing or outright eliminating the production of those that aren’t selling well. Over time, a few of the kinds of products in this group which best fit the preferences of the buyers and the ability of the producers to make them. These products will dominate the market until the preferences of the buyers or the ability of the producers to produce them change [example: a shortage in the price of a particular material needed for a popular product].

You have most likely observed this process in the “news topic” context yourself, where it tends to happen much faster as “cheap and easy” news stories are happily picked up by news agencies to broadcast until people get sick of them and tune out.

This can all, hopefully, be understood as a purely logical outcome – a conclusion that universally and necessarily follows from the premises given. There should be nothing supernatural or even surprising here, is there?

So, now that you understand why and how evolution works (if you didn’t before), I can move on. (Incidentally, the part of the example above that describes a computerized system is actually referred to as a “genetic algorithm”.)

My purpose in starting with this is because it really and truly is fundamental to the topic that I expect to spend most of this week posting about, and which has been of vital importance to human culture and intellectual development for thousands of years. This most important subject involves such notable figures as Charles Darwin,St. Thomas Aquinas, Noted American Science-guy Benjamin Franklin, New England Puritan Cotton Mather and Quaker William Penn ,Hardcore Catholics like Pope John Paul II, Hardcore Athiests like PZ Myers, even famous religious figures like Jesus.

I refer, of course, to wine (and beer and other examples of ethanol production).

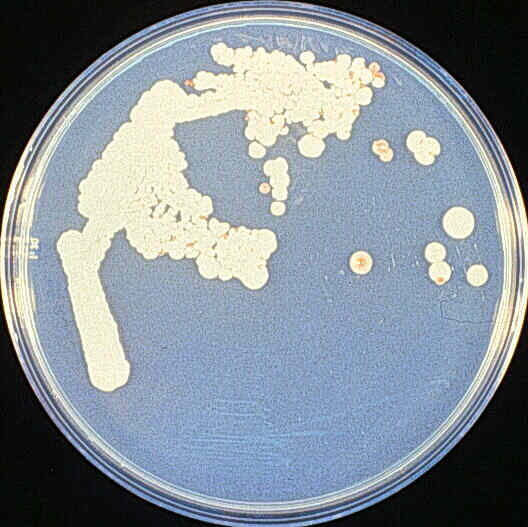

Okay, here’s the background: I just graduated with my B.S. in Microbiology, and I’ve got this whole “Hillbilly Biotech”/”Do-it-yourself”/”Practical Science” kind of thing going on in my interests. That being the case, I wondered what it would take to isolate, culture, and maintain my own yeast (and bacteria – more on that later) stocks from the environment rather than buying “canned” cultures – or at least play with the “canned” yeasts to create my own stocks. As I was poking around, though, I kept running into the same attitudes – namely that it’s “too hard” to do this, and although there are a number of people who advocate re-culturing canned commercial yeasts for a short time to save money, none of them think it’s feasible to do this for more than a couple of generations, at which point we are assured that you have to go buy it again or else “mutations” will inevitably appear and scary and mysterious “off-flavors” will result and the brewing police will come and throw you in jail for deviating from the archetype of whatever pre-defined style of wine or beer you’re trying to make. Or something like that. In any case, it’s because of this fear of “mutations” that I am starting out with this “evolution”-related post: in biological evolution, various forms of alterations in the genetic material are the “changes before or during copying” in the gedanken experiment above.

I didn’t buy it when people were telling me that it was “too hard” to learn how my computer works so that I could run Linux and should instead leave deciding what my computer should do to the “professionals”, and I’m not buying the same argument about commercial yeasts, either. If I felt that way, I might as well leave the rest of the complex technology of brewing to the “professionals” too, and consign myself to “Lite Beer” and “Thunderbird” for the rest of my life.

I’ve been spending much of the last few weeks perusing books, online articles, and scientific papers on subjects related to brewing in general and brewing yeasts in particular, and this should form the bulk of this week’s post topics, of not well beyond this week. Tomorrow I intend to start in on the actual process of culturing yeasts. Meanwhile, feel free to correct my no doubt horribly over-simplified explanation of evolutionary processes in the comments.

It’s slow going trying to get the mess up here in Idaho organized in preparation for the move to Texas, but I did manage to sacrifice a large number of my old books that I no longer need. Trading them in at the local representative of the “Hastings” bookstore chain got me a decent amount of store credit, and I was able to special-order this wine microbiology book I’ve been lusting after for months. It showed up a couple of days ago.

It’s slow going trying to get the mess up here in Idaho organized in preparation for the move to Texas, but I did manage to sacrifice a large number of my old books that I no longer need. Trading them in at the local representative of the “Hastings” bookstore chain got me a decent amount of store credit, and I was able to special-order this wine microbiology book I’ve been lusting after for months. It showed up a couple of days ago. Prior to that, I picked up a book I found at the local brewing-supply place in The Woodlands, Texas. It’s an entire book on the subject of Belgian and “Belgian-style” beers (like Lambic) fermented with “wild” yeasts and bacteria. It’s an excellent mix of history, science, travelogue, and “how-to”. I highly recommend it.

Prior to that, I picked up a book I found at the local brewing-supply place in The Woodlands, Texas. It’s an entire book on the subject of Belgian and “Belgian-style” beers (like Lambic) fermented with “wild” yeasts and bacteria. It’s an excellent mix of history, science, travelogue, and “how-to”. I highly recommend it.